If you visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem today, you are bound to encounter friars dressed in brown robes. That is, you are bound to see members of the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, a Catholic Christian monastic institution established in the fourteenth century to care for pilgrims and pilgrimage sites in and around the Holy City. How did these friars take on this role and what sorts of challenges did they encounter in forming the Custody? These are some of the questions I sought to answer while completing my dissertation in Jerusalem with Fulbright Israel. Through the examination of various documents — including unpublished medieval manuscripts — I sought to explain the earliest years of the Custody’s founding, contextualizing it within the wider environment of the late medieval Mediterranean.

During the time of the Crusades (c.1100-1300), Latin Christians maintained direct control of many cities and shrines in the Holy Land. The fall of the last major crusader stronghold in 1291, however, vastly redefined this Latin connection to the Levant. Though additional crusades were called, none brought about a Christian re-conquest of the land. Only a small group of Franciscans effected the re-establishment of a lasting Latin presence in and around Jerusalem.

Seeking to care for Christian holy sites in the city, these friars founded a monastery on Mt. Sion in the 1330s, using it as a base to conduct their custodial work throughout the region. By the end of the century, they had gained privileges of custodianship at the Holy Sepulcher, Bethlehem, and several other shrines. Nonetheless, their intended task was constantly beset with trials, situated as it was within a complex network of political, religious, and economic realities of the wider Mediterranean.

As caretakers of the holy sites, the Franciscans formed relationships — some more congenial than others — with a wide array of leaders and communities, including: Latin Christian monarchs from Spain and Italy, popes living in Avignon, Mamluk sultans reigning from Egypt, Islamic officials in Jerusalem, members of Eastern Christian communities (Armenians, Georgians, Greeks, etc.), and of course Latin pilgrims. Each relationship presented the friars with different challenges and opportunities, and most of these relationships overlapped in some form or fashion, creating a complicated web of interfaith interactions.

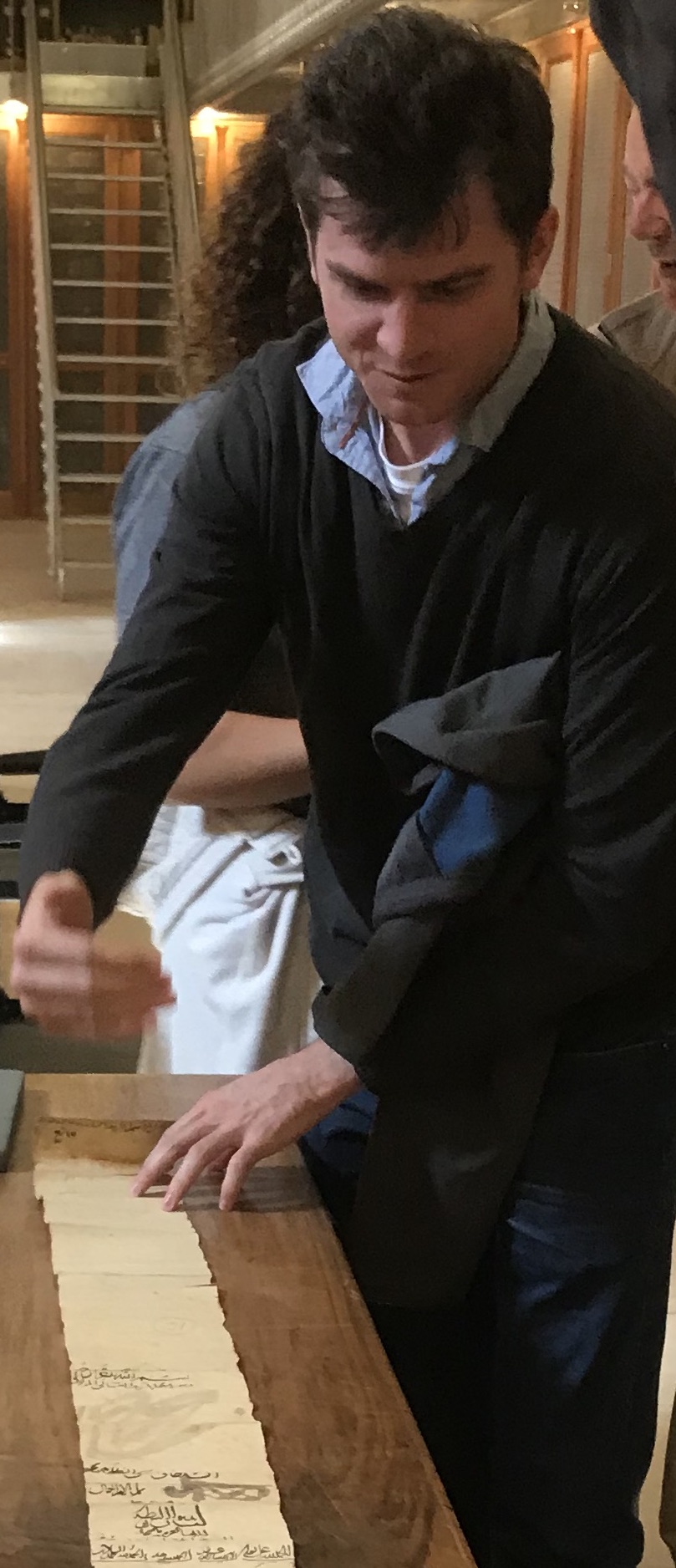

A couple of examples will help to illustrate this point. The first pertains to the friars’ acquisition of property in the Holy City. In 1372, the Franciscans purchased land on Mt. Sion for the sake of continuing the custodial work they had begun earlier in the century. The event is recorded in a Mamluk deed of purchase — an Arabic document housed today in the Franciscan Archive of the Holy Land. According to this deed, a certain friar, Anthony, purchased property from the local treasury in Jerusalem.

Alone, this economic exchange is an intriguing instance of late medieval Muslim-Christian relations, but it becomes far more significant when seen within a broader context. Brother Anthony did not conduct his business without help. The deed notes that his purchase was carried out with the assistance of Joanna of Naples, queen of a powerful Catholic kingdom in southern Italy. Indeed, according to another document — an embassy record from a few years earlier — Joanna had petitioned the sultan in Egypt to maintain the friars’ safety and rights to reside in Jerusalem.

But why did the queen bother to offer her patronage to the friars? For Joanna and several other Catholic monarchs, supporting the Franciscans in the Holy Land was simultaneously a way of advancing a Latin Christian cause in the Levant without undertaking the more costly enterprise of a crusade and a means of establishing profitable trade relations with the Mamluks. According to papal regulations at the time, trade with and travel to Islamic lands was generally forbidden. By supporting the cause of the Custody, however, kings and queens could receive a special license from the popes, allowing them to conduct negotiations and trade with Egypt. Thus, by closely studying a single purchase of property, we tap into many of the interfaith complexities of the wider Mediterranean world.

A second example illustrates much the same. Not long after brother Anthony’s purchase of land, Sultan Barquq of the Mamluk Empire issued a series of decrees from Cairo on behalf of the friars. According to these decrees (also housed in the Franciscan archive today), the friars had complained to the sultan that their privileges at the Holy Sepulcher had been violated by both Mamluk officials and local Eastern Christian communities (Georgians and Greeks specifically). Sultan Barquq replied that the friars should suffer no harm and their rights should be protected.

Why were the friars running into conflicts with Mamluk officials and Eastern Christians? In the case of the Mamluks, these officers may have simply robbed or harassed the Franciscans for petty personal reasons, but importantly, attacking the friars was also a means of challenging the power of the sultanate. By granting the Franciscans permission to reside in the Holy Land, the sultans — ruling from Egypt — essentially transformed the friars into an embodiment of their own regal authority in the distant environs of Jerusalem. Consequently, the Custody was positioned dangerously within the frequent conflicts that erupted between the sultans in Cairo and their subordinates in the region around Jerusalem. As for Eastern Christians, they too were interested in caring for the holy sites and also sought privileges from the Mamluks. In their work at the Custody, therefore, the friars had competition, even with other Christians. The history of the Franciscans’ work is again connected to a wide array of interreligious relations.

Thanks to Fulbright Israel, I was able to study these many interweaving facets that formed the founding of the Custody. Not only did I have the incredible opportunity to examine medieval manuscripts and to complete my dissertation, but, through this work, I came to a clearer understanding that complex interfaith relations must be viewed within a wider framework of religious, political, and economic realities.

Articles are written by Fulbright grantees and do not reflect the opinions of the Fulbright Commission, the grantees’ host institutions, or the U.S. Department of State.